Protecting the glass sponge reefs

As incredibly beautiful and unique as the glass sponges are, they are also equally fragile. Although the sponge reefs have survived for 9,000 years, human activities now damage and threaten the glass sponge reefs and all the other animals that live among them. In 1999 during a survey of the reefs scientists noticed large areas of the reefs that were completely destroyed by bottom trawling and other harmful fishing activities.1

Heavy fishing gear can completely crush the delicate skeletons of the sponges. Fishing gear also churns up mud and sand from the seabed creating sediment clouds that smother the sponges. This prevents the sponges from getting the oxygen and food that they need to survive and grow.

Join the List

CPAWS-BC is working to ensure that glass sponge reefs receive the protections they deserve. Sign up now to get the latest conservation news and updates right to your inbox.

Glass sponges are very slow growing – it is estimated that a one metre tall sponge may be 220 years old 2 and a patch of reef may take hundreds of years to recover from damage, if they ever recover at all. For many years, conservationists, fishermen, scientists, and the Canadian government have been working together to protect the reefs by creating a marine protected area within which no harmful activities will take place.

Broken Glass

Unfortunately, scientists believe that by the time the reefs were discovered in 1987, fishing activity had already destroyed half of them.1 Bottom trawling fishing boats drag huge nets weighing up to two tonnes along the seafloor, crushing and catching everything in their path, leaving only rubble and clouds of sediment behind. Weighted prawn and crab traps drop to the seabed like bombs, leaving craters where they land. The fragile silica skeletons of the glass sponges have the texture of baked meringue (or a prawn chip if you prefer savoury), and so are easily crushed by even minimal contact.

Maps of the areas targeted by bottom trawling fishing show the black scars of their “tracks” right over the glass sponge reefs.1,3 Fishing boats unknowingly targeted the reefs, causing great damage. It makes sense that the sponge reefs are good fishing grounds for prawns, rockfish, halibut, and cod because they provide such good habitat for them. It is also for this very reason that the reefs need strong protection – they are important for maintaining healthy populations of many sea creatures that many of us depend on for food and jobs.

Sediment clouds smother the reefs

When heavy fishing gear, cables and anchors are dragged along the seafloor, even if they do not crush the sponges directly, they can damage the sponges by stirring up thick clouds of mud and sand (sediment) from the seabed. When these clouds are swept over the sponges they smother them, blocking the pores that cover the surface of the sponge and stopping them from filtering oxygen and food from the water.4

When this happens glass sponges can send electrical signals that stop feeding (similar to how our nervous system tells us to hold our breath underwater). In the short term, this stops the sponge from choking on sediments and helps them to survive.4 If the activity stops and water clears, the sponge can start feeding as normal in about six hours. However the sponge has effectively “skipped a meal” and lost some much needed energy. If activities that stir up sediment clouds happen often the sponges could stop feeding for so long that they begin to starve, slowing their growth and ability to reproduce. If activities that re-suspend sediment continue for long periods of time scientists believe that the sponges will eventually die of starvation. Because the sponges rely on water currents to feed, scientists have estimated that if a sponge is exposed to sediment when the current is at its peak, it will reduce the amount of food they can consume by two-thirds4, so instead of three meals a day the sponges only get to eat breakfast.

In 2019, research conducted by Dr. Sally Leys’s lab concluded that sediment from a far away as six kilometres can affect the feeding of glass sponges in the Hecate Strait.8

Establishing the Hecate Strait/Queen Charlotte Sound Glass Sponge Reefs Marine Protected Area

BC’s glass sponge reefs are incredibly rare, ancient and important ecosystems. The Hecate Strait and Queen Charlotte Sound Marine Protected Area provides these reefs with permanent protection, prevents further damage and ensures the reefs can remain a source of awe and wonder for generations to come.

When fisherman and conservationists recognised the significance of the reefs and realized that they were in danger, work began to establish fishing closures to protect the reefs from more accidental damage. In 2001 voluntary closures were put in place by the fishing industry to stop bottom trawling over the reefs and in 2002 created mandatory closures through regulation, so that it is now illegal to bottom trawl over the reefs.5

But stopping bottom trawling on the reefs was a first step, as the reefs were also at risk from prawn and crab trap fisheries, mid water trawling, and bottom trawling next to the reefs that can create harmful sediment clouds, and accidentally crush the reefs if the gear is not placed perfectly. There were many other threats unrelated to fisheries, including the laying of underwater cables, dumping at sea, and bitumen (heavy) oil spills. After years of campaigning by CPAWS, in 2010 the government of Canada announced that the Hecate Strait and Queen Charlotte glass sponge reefs as an area of interest for a marine protected area.6

Five years later, in June 2015 government of Canada released the proposed regulations for the glass sponge reef MPA to the public and asked for feedback.7 CPAWS welcomed this as an important step in establishing the MPA but had some concerns that the proposed management plan wasn’t strong enough, and potentially harmful activities like trawling would still be allowed around the reefs.

Over the 30 day comment period the government of Canada received feedback from thousands of people, including a letter signed by 40 international scientists stating that the risks were simply too great to allow potentially harmful activities like trawling, anchoring, and laying cables to occur in the adaptive management zones.

Conservation groups were thrilled to hear Canada’s glass sponge reefs were fully protected on February 16, 2017 in the form of a Marine Protected Area. The Hecate Strait and Queen Charlotte Sound Glass Sponge Reefs Marine Protected Area was announced by Minister of Fisheries, and the Canadian Coast Guard, Dominic LeBlanc.

Making the glass sponge reefs a marine protected area (or MPA for short) means that all uses of the ocean over and around the reefs are assessed and all potentially harmful activities are properly managed according to a comprehensive management plan. The MPA prohibits all bottom contact fishing activities from occurring within at least 1 kilometre of the reefs, until it can be proven that activities are not harmful. Additionally, Fisheries and Oceans Canada will implement more stringent measures for midwater trawl fisheries through fisheries closures.

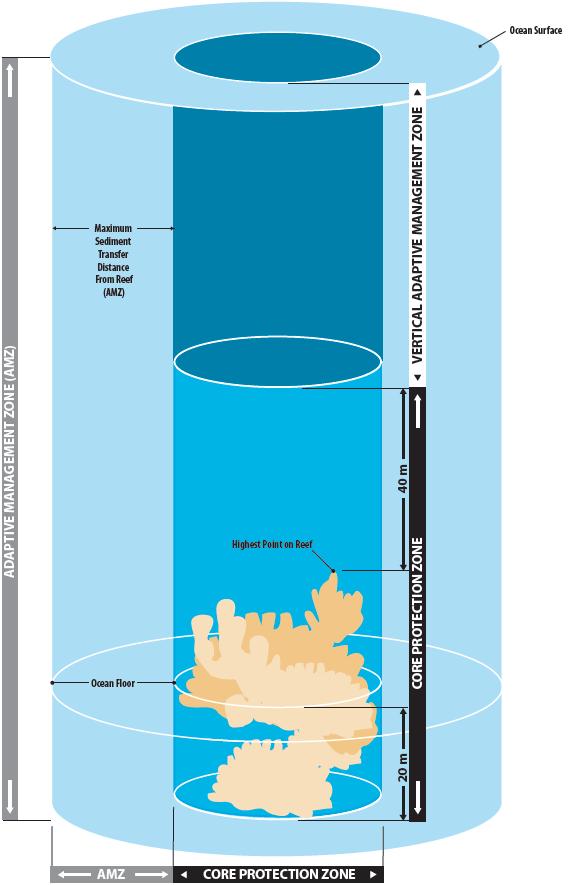

Each glass sponge reef has a Core Protection Zone, a Vertical Adaptive Management Zone, and an Adaptive Management Zone.

Credit: Fisheries and Oceans Canada

- The Core Protection Zones contain the sponge reefs and are designed to provide the highest level of protection to the reefs. The Core Protection Zone consists of the seabed, the subsoil to a depth of 20m and the water column above the seabed to a depth of 100 m below the sea surface for the Northern Reef, 120 m for the Central Reef, and 146 m for the Southern Reef.

- The Core Protection Zones are closed to all commercial, recreational, and Aboriginal fishing. Anchoring and cable installation, maintenance, and repair are also prohibited in the Core Protection Zones.

- The Vertical Adaptive Management Zones consist of the water column that extends above the Core Protection Zones to the sea surface.

- The Adaptive Management Zones consist of the seabed, subsoil and waters of the Marine Protected Areas (i.e., Northern, Central, and Southern Reefs) that are not part of the Core Protection Zones or the Vertical Adaptive Management Zones.

- The Vertical Adaptive Management Zones and Adaptive Management Zones are currently closed to all commercial bottom contact fishing activities for prawn, shrimp, crab, and groundfish (including halibut), as well as for midwater trawl for hake. These closures will be in effect until further notice.

CPAWS is pleased to see the Government of Canada take the necessary steps to improve the protection of the reefs and congratulates the government for taking a much more precautionary approach to conservation.

Strait of Georgia and Atl’ka7tsem/Howe Sound Glass Sponge Reef Conservation Initiative

In 2015, nine glass sponge reefs in the Strait of Georgia were closed to commercial, recreational or Indigenous Food, Social and Ceremonial bottom-contact fishing activities.

In 2019, nine glass sponge reefs in Atl’ka7tsem/Howe Sound were protected with eight refuges prohibiting commercial, recreational or Indigenous Food, Social and Ceremonial bottom-contact fishing activities. The use of downrigger gear in recreational salmon trolling is also prohibited in these areas due to the potential risk of damage to shallow reefs.

In 2021, five more glass sponge reefs Atl’ka7tsem/Howe Sound were protected with fishing closures. All known reefs are now protected with refuges and fishing closures.

CPAWS-BC is now working to make these protections more permanent and to increase the strength of monitoring and enforcement.

To see a timeline of the glass sponge reefs, including discovery and protection, click here!

Join the List

CPAWS-BC is working to ensure that glass sponge reefs receive the protections they deserve. Sign up now to get the latest conservation news and updates right to your inbox.